As I look back at some of the things I have done this year now ending, I am struck by their implications for historiography.

One of those things was a journey through the Dudley canal tunnel. These take place regularly and are organised by the Dudley Canal Trust. The Dudley Canal Trust has been with us since the 1960s, and was formed with the aim of restoring the then-disused tunnel. I have before me a booklet published to commemorate the reopening of the tunnel on 21 April 1973, an occasion dubbed TRAD (Tunnel Reopening at Dudley) Weekend. Derek A. Gittings, who contributes the booklet’s account of the restoration writes that when commercial traffic through the tunnel ceased “In terms of conventional history, Dudley Tunnel had spanned the years between the French Revolution and the Second World War.” Why should events like these be the markers of conventional history? The tunnel’s own history is fascinating enough.

What is more, TRAD itself is now part of history. In 1944 Parliament had declared many more or less disused waterways officially abandoned. Waterway enthusiasts nonetheless kept the faith that the system would flower again for pleasure cruising and that many of the abandoned canals could be restored. Dudley, though, was something else. Official abandonment did not come until 1962; little more than a decade later the Dudley canal and tunnel were reopened. This was thanks to the combining of determined voluntary effort, by cavers as well as waterways enthusiasts, with the support of local government and of commerce so that, for example, heavy plant and building materials could be afforded. This was an early example of a collaboration that has since become common: for example in the end-to-end restoration of the Huddersfield Narrow Canal and Standedge Tunnel. It is now recognised that restored and flourishing canals are not merely somebody’s hobby but make for pleasant and lively communities and contribute hugely to local economies.

The commemorative booklet, produced mainly as a souvenir, is now a historical document. The black and white photographs; the telephone numbers quoted in a boat-hire company’s advertisement (“Shardlow 732”); that the Mayor of Dudley, who with the Chairman of the British Waterways Board performed the opening ceremony, was an Alderman (the office was abolished the following year) – all show that 1973 was a long time ago. And the whole story shows that the particular and the local can be epoch-making.

The tunnel itself is perhaps the most ethereal structure on the entire inland waterway system. Some of it is lined with brick,

some, post-restoration, with concrete, and some is bored through bare rock.

and some is bored through bare rock. And that rock is often fascinating.

And that rock is often fascinating.

A transition from rock to brick

A transition from concrete to rock

It is not simply a tunnel but has also numerous branch tunnels and old mine workings.

and old mine workings.

It is no wonder that cavers as well as canal enthusiasts valued it. Go and see for yourself.

It is no wonder that cavers as well as canal enthusiasts valued it. Go and see for yourself.

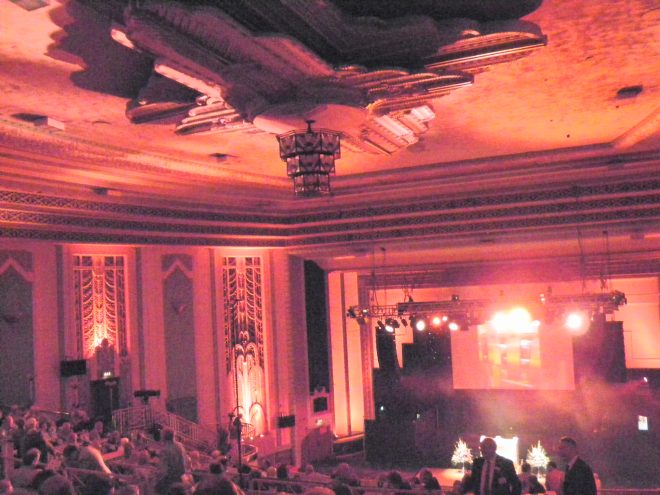

The sheer size impresses – and the auditorium was well-filled – but just because of the size the astonishingly clear acoustic is a pleasurable shock. At one point the microphone through which Richard Hills was announcing his items failed; he used his unamplified voice instead but was still clearly audible to me in one of the further-flung rows on the balcony. The exuberance of the decoration testifies to the exuberance of the mind which created it. I like to think of the effect of both scale and spectacle on those who appreciated it in its heyday as a cinema. What leap of mind and spirit there must have been when those used to their local fleapit came here. There could be no more fitting home for the Trocadero Wurlitzer: a home of the kind, and on the scale, it was designed for.

The sheer size impresses – and the auditorium was well-filled – but just because of the size the astonishingly clear acoustic is a pleasurable shock. At one point the microphone through which Richard Hills was announcing his items failed; he used his unamplified voice instead but was still clearly audible to me in one of the further-flung rows on the balcony. The exuberance of the decoration testifies to the exuberance of the mind which created it. I like to think of the effect of both scale and spectacle on those who appreciated it in its heyday as a cinema. What leap of mind and spirit there must have been when those used to their local fleapit came here. There could be no more fitting home for the Trocadero Wurlitzer: a home of the kind, and on the scale, it was designed for.

and some is bored through bare rock.

and some is bored through bare rock. And that rock is often fascinating.

And that rock is often fascinating.

and old mine workings.

and old mine workings.

It is no wonder that cavers as well as canal enthusiasts valued it. Go and see for yourself.

It is no wonder that cavers as well as canal enthusiasts valued it. Go and see for yourself.